The very first AI system, a Neural Network, was not built for language or code. It was not trained on internet-scale data. It was a simple machine created in 1957 by Frank Rosenblatt, called the Perceptron, assembled from motors, wires, and a grid of photocells. It learned from crude, low-resolution images projected onto a board of light sensors.

It could only learn very simple patterns, yet it introduced a new idea: instead of programming rules directly, we can train a machine by showing it examples.

Neural networks evolved slowly. Minsky and Papert documented the limits of the Perceptron in 1969. Backpropagation revived the field in the 1980s (Rumelhart et al.). Convolutional nets gained traction in the 1990s (LeCun). Deep learning reached mainstream credibility after AlexNet in 2012.

The Transformer architecture (Vaswani et al., 2017) shifted the field's focus from images to sequences, enabling models to process and generate language at scale, which opened the door to general-purpose reasoning systems.

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT) emerged as the standard approach: collect labeled data, train the model to predict outputs from inputs. This worked for classification, translation, and eventually language generation. But complex sequential tasks required a different approach.

Reinforcement learning, which had roots in control theory and animal behavior research from the 1950s, offered a solution. Instead of learning from static demonstrations, agents could learn from trial and error; taking actions, observing outcomes, and optimizing for rewards. DeepMind's DQN playing Atari games (2013) and AlphaGo defeating world champions (2016) demonstrated RL's potential for complex decision-making.1

By the early 2020s, researchers began combining both paradigms: SFT to bootstrap from human demonstrations, then RL to refine behavior through interaction.

In 2025, multimodal models2 like Claude 4.5 Sonnet can take a screenshot as input, parse the layout, understand what is interactive, and return structured actions such as:

"output": [

{

"type": "reasoning",

"id": "rs_67cc...",

"summary": [

{

"type": "summary_text",

"text": "Clicking on the browser address bar."

}

]

},

{

"type": "computer_call",

"id": "cu_67cc...",

"call_id": "call_zw3...",

"action": {

"type": "click",

"button": "left",

"x": 156,

"y": 50

},

"status": "completed"

}

]This is no longer simple classification. It is perception, reasoning and action in a single loop.

In other words, the same idea demonstrated in 1957 has become the basis for agents3 that can now operate computers. Pixel trained models can interpret websites, identify buttons, understand form fields and decide what to do next. Combined with structured outputs, they can complete digital tasks that used to require a human sitting at a keyboard.

A machine that once recognized simple shapes and curves is now helping build more advanced machines that can use software.

What are “computer use models”?

Alright so, what exactly is “computer use”?

A computer use model (sometimes called a “computer use agent”) is a vision language model that is trained to use a computer. It knows to interact with software via the standard user interfaces we humans use: clicks, keystrokes, scrolls, screens, and windows.

The key point is that the agent does not require programmatic APIs or backend integrations. It uses the frontends that already exist, such as web browsers and GUI applications.

Why is that important?

Traditional automations such as macros, RPA and custom scripts often requires specially built connectors or brittle scripts. Computer use models promise general purpose automation across many apps without custom integrations. Their interface is the one humans already use, and such agents can scale to various tasks and domains out of the box.

When developing autonomous vehicles, Tesla faced a choice: either rebuild roads with special sensors, markers, and infrastructure designed for robots, or train AI models to navigate the messy, imperfect roads that already exist. Tesla chose the latter, training their models on real-world conditions: faded lane markings, unexpected obstacles, human drivers behaving unpredictably, and roads in every state of repair or disrepair.

Computer use models follow the same philosophy for the digital world.

Rather than waiting for every website, application, and system to be rebuilt with clean APIs and AI-friendly interfaces, these models learn to navigate the internet and software as it exists today: clicking buttons, filling forms, reading screens, and adapting to inconsistent interfaces, just as humans do. The "roads" are the legacy systems, outdated interfaces, and countless applications that will never be modernized. The AI learns to drive on them anyway.

This opens the door to a new class of AI and software interaction where the human role shifts from direct operation to supervision and orchestration.4

The two paths: vision-based vs. text-based agents

When you build a system that uses software like a human, there are two fundamental ways for it to perceive and act. One is by “seeing” the literal screen itself (vision). The other is by reading the interface structure (DOM, accessibility trees, or similar).

Let’s dive into both.

Vision-based models

How they work

Visionbased agents treat the interface as images or video frames. They receive screenshots, process them with vision, and output actions/tool calls such as "click at (x, y)", "type this text", "scroll down". The models are trained on a set viewport (ie 1288 x 711 or 1024 x 768) and can identify interact-able objects within a screenshot and find the exact pixel on the screen to interact with.

What are they good at?

Since the agent uses the same visual interface as a human does, it can in principle operate any UI in existence: browsers, desktop apps, mobile apps, legacy tools with no API support, and so on. The model mimics how a human operates, and can handle unfamiliar sites or applications that were not in the initial training data.

What is the tradeoff?

But Vision processing is expensive. Interfaces change. Layout shifts, colors change, elements move a bit. The model can misinterpret what is clickable or where something is on screen. The models are also trained for accuracy on a very specific viewport/aspect ratio so any changes and the model effectively breaks.

Also, a screenshot does not always reveal internal state. For example, whether a form field is valid, or whether a button is disabled. The agent may need repeated observations or trial and error. For many tasks, seeing everything is overkill when structure is available. Vision often adds latency and increased token cost compared to textual representations.

Examples:

OpenAI’s Operator is an example of a “computer use agent”. The AI took screenshots and returned mouse and keyboard actions which are translated to Playwright. It required no specialized integration into the target application, because it worked with what a human user would see. Under the hood their product uses the computer-use-preview model, which was trained specifically to interact with pixels on the screen.

We (Browserbase) built an open source implementation of Operator for people to experiment with the model and see how it works.

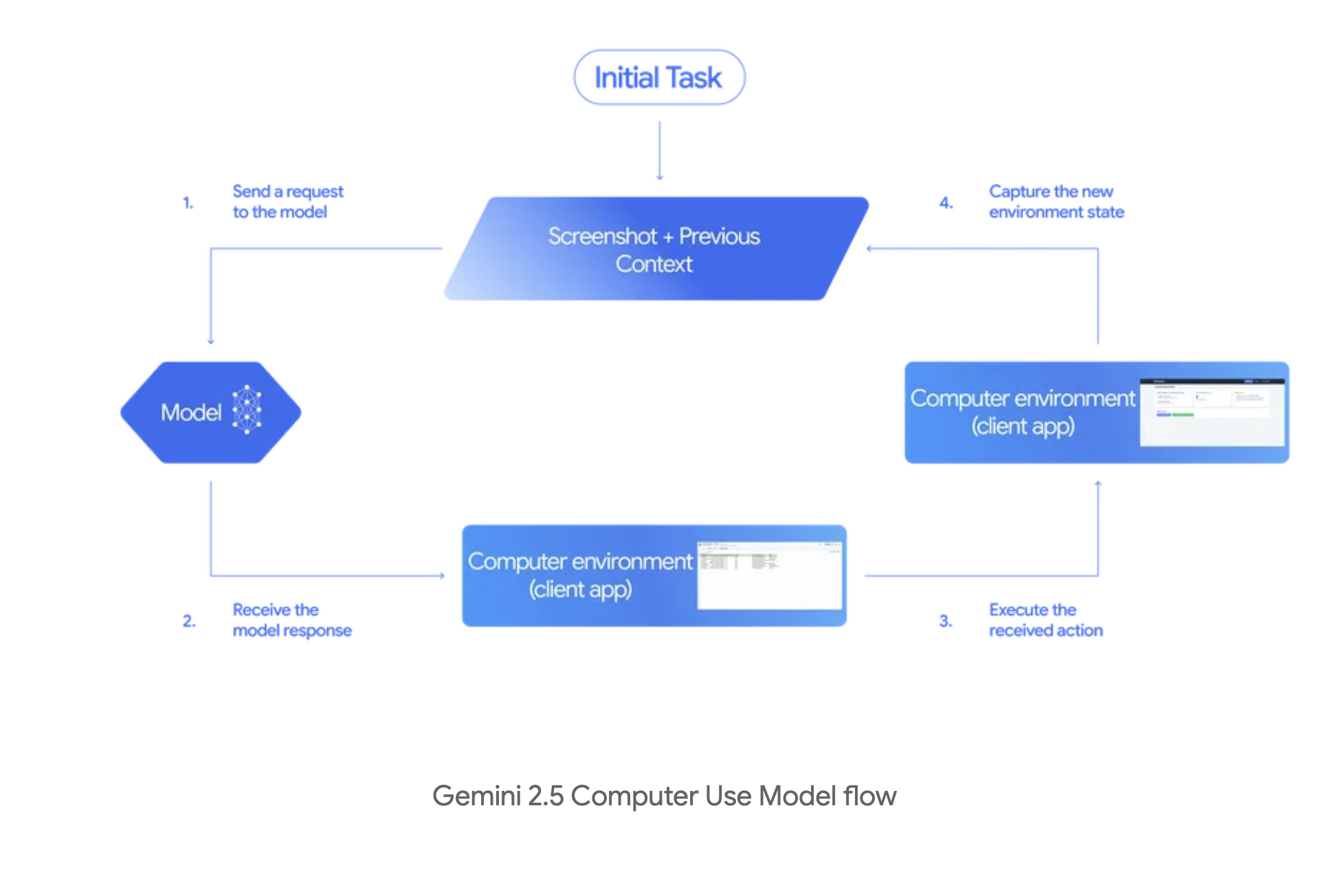

Google DeepMind’s Gemini 2.5 Computer Use model works similarly. Screenshots go in, actions (with reasoning traces) come out. This model differs slightly from the one from OpenAI, in that it will return multiple actions at once (assuming future browser state) so the agent harness is able to complete them sequentially, leading to net faster execution of tasks.

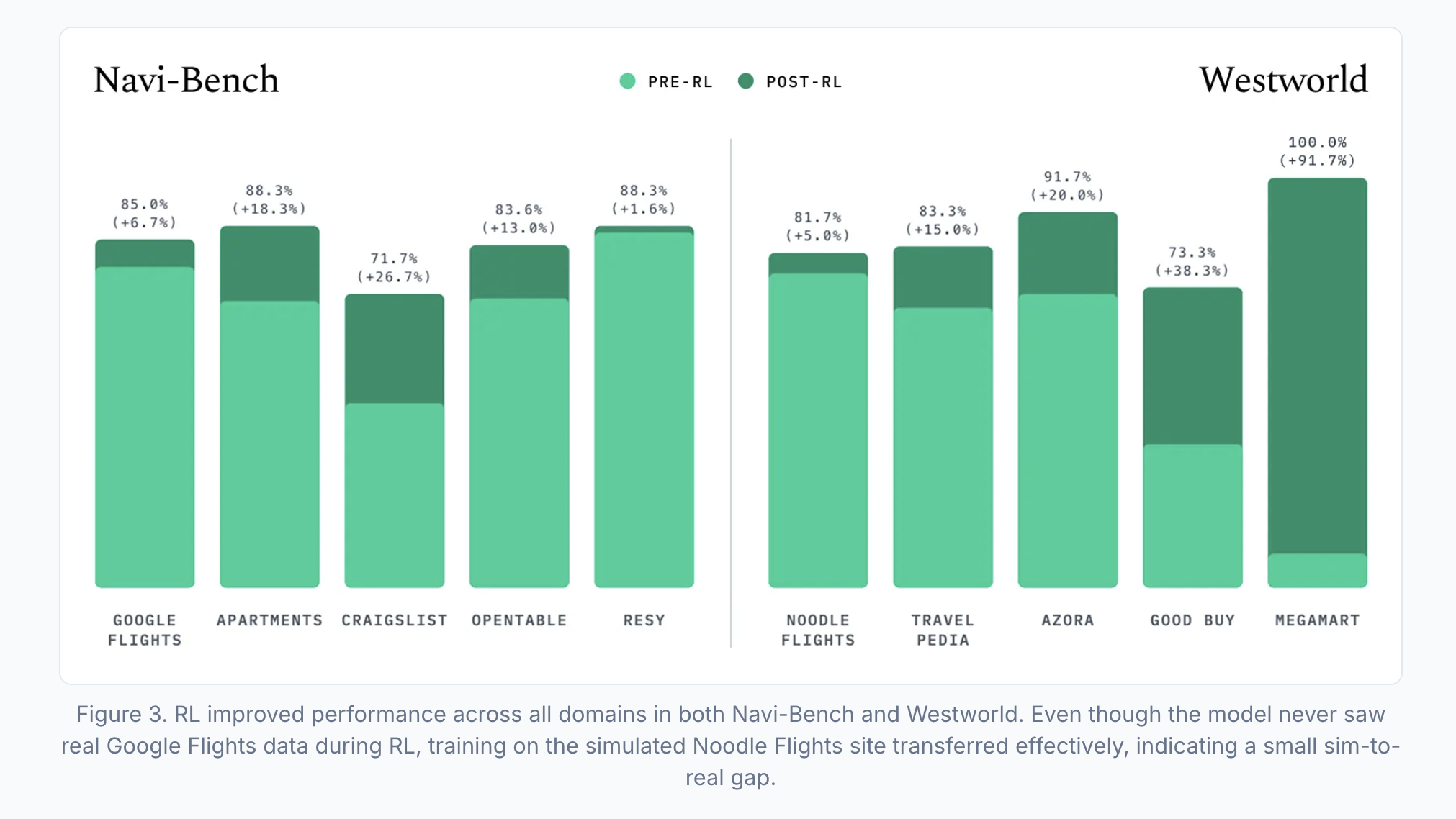

Yutori’s n1 is SOTA on their custom benchmark5 Navi-Bench. They’re fully bought in on vision models being the future of computer-use, and used Qwen3-VL as the base-model for n1. Their approach relies heavily on mid-training the model on a wide breadth of navigation trajectories including unsuccessful and noisy approaches to broaden knowledge and general understanding of the web as a whole. The model is then subsequently trained via SFT on clean and successful trajectories, then undergoes a RL stage using GRPO; an optimization policy made popular by Deepseek.

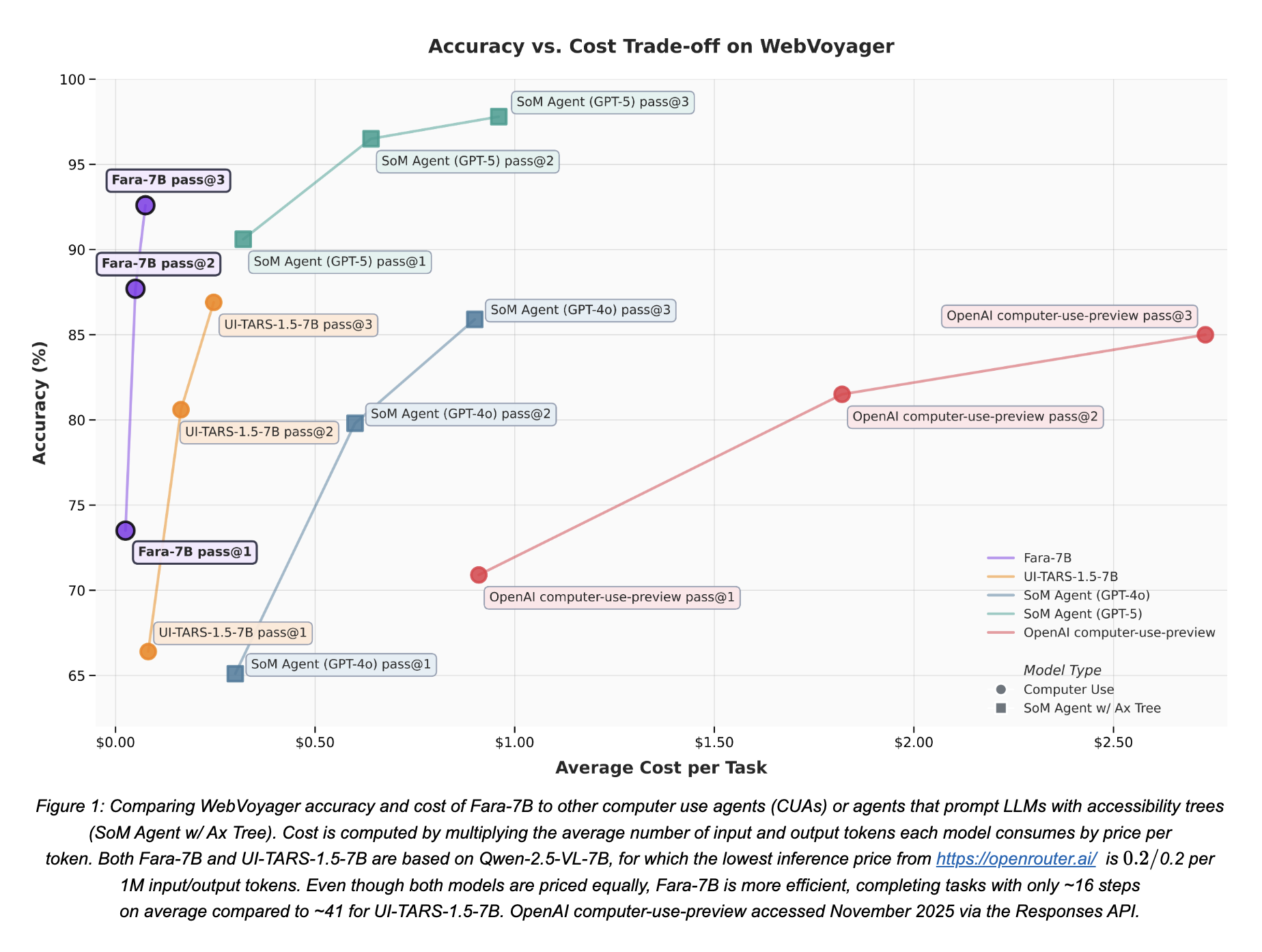

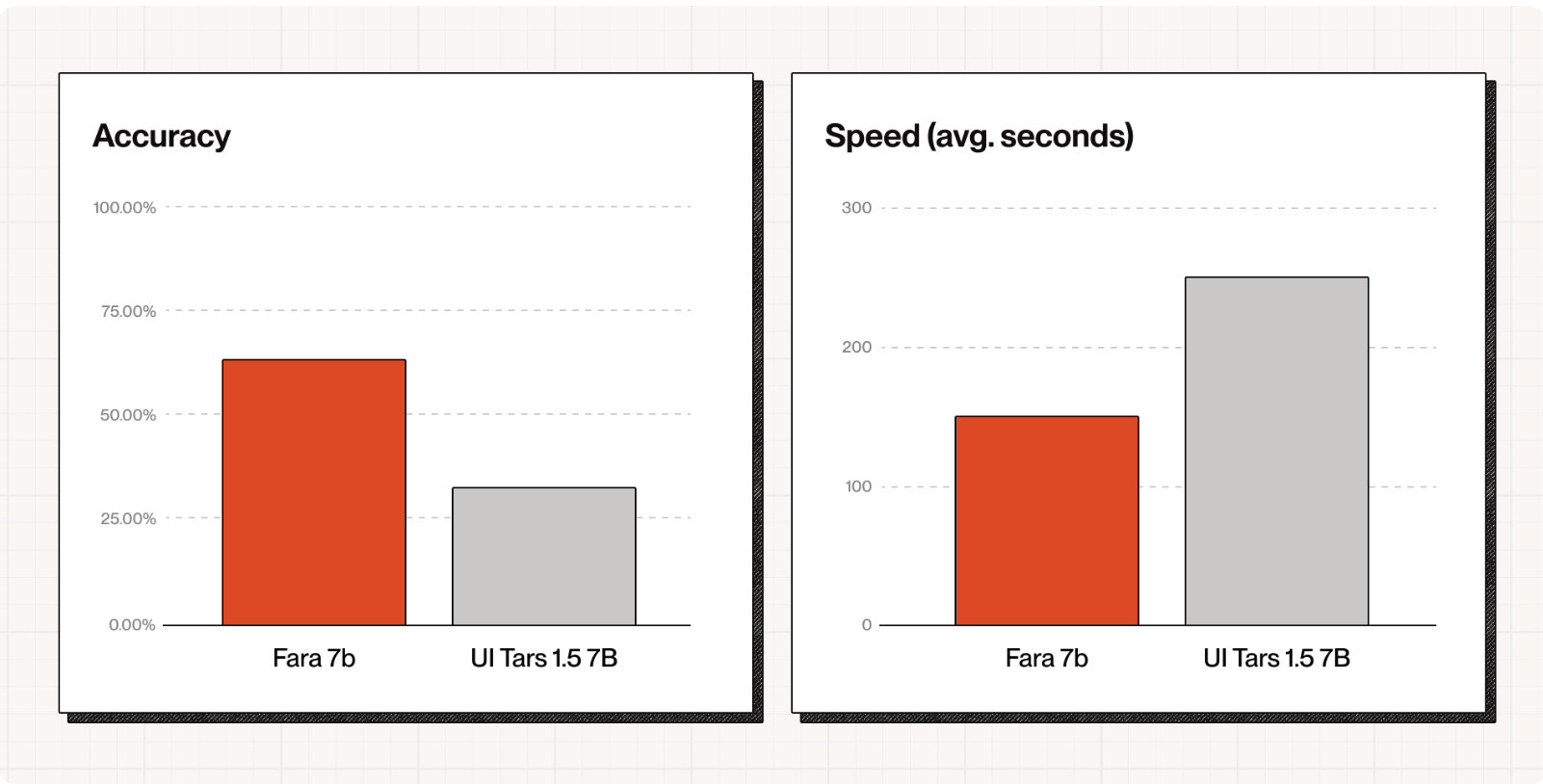

There’s also frontier research on SLMs for Computer-use. Fara-7B from Microsoft is a small but mighty computer use model meant to be deployed and run directly on every Windows 11 machine. The model is a Qwen2.5-VL fine tune, trained using SFT with data from an experimental CUA multi-agent synthetic data generation pipeline. The system uses one AI agent to propose diverse web tasks, another multi-agent system Magentic-One to attempt solving those tasks and generate step-by-step demonstrations, and finally three verifier agents to check if the solutions were successful, creating a large synthetic training dataset without needing human annotators.

This yielded SOTA performance within the model’s size class, outperforming UI-Tars-1.5 and OpenAI’s computer-use-preview model on the WebVoyager benchmark.

Here's a quick start to get you up and running and deploying Computer use models in production.

npx create-browser-app@latest -t gemini-cuaThen running the agent itself in code is simple.

const agent = stagehand.agent({

cua: true,

model: {

modelName: "google/gemini-2.5-computer-use-preview-10-2025",

apiKey: process.env.GOOGLE_API_KEY

},

systemPrompt: "You are a helpful assistant that can use a web browser."

});

const result = await agent.execute({

instruction: "Tell me what Stagehand.dev does."

});Text/DOM Based Agents

How they work

Instead of looking at pixels, a text-based agent accesses the internal representation of the UI: the HTML DOM tree, accessibility snapshots, roles, labels, attributes, event handlers, and so on. It reasons over that structure (“there is a button labeled ‘Submit’ under a <form> element”) and then invokes automation primitives to take action in a webpage.

For example, Stagehand (our open source web automation framework), takes a snapshot of the DOM and accessibility tree, parses it using an LLM, and then decides what actions to take based on the webpage structure.

If you try the example on the Browserbase landing page, you'll see the raw HTML is a whopping 27k tokens6, while our truncated DOM/A11y tree is only 6k. Research shows LLMs are able to make better decisions when their context isn't clogged with unnecessary information, so Stagehand's custom snapshot is key to better-performing agents.

What are they good at?

Structured data typically provides fewer ambiguities. You can target a specific element instead of guessing a position on screen, improving reliability and speed. Instead of sending full images to the model, you can send a compact version of the DOM subtree, reducing tokens, latency and cost.

And the more you look at how the web is actually built, the more natural this form factor becomes. Web automation is often inherently structured: Forms, tables, lists, search results and dashboards are all built from elements with attributes and are a natural fit for text-based Agents.

What are the tradeoffs?

The model may know there exists a <button id="buy">Buy</button> but not whether it is visible, covered by a modal, off-screen, or partially obscured. Visual context can still matter in a lot of tasks.

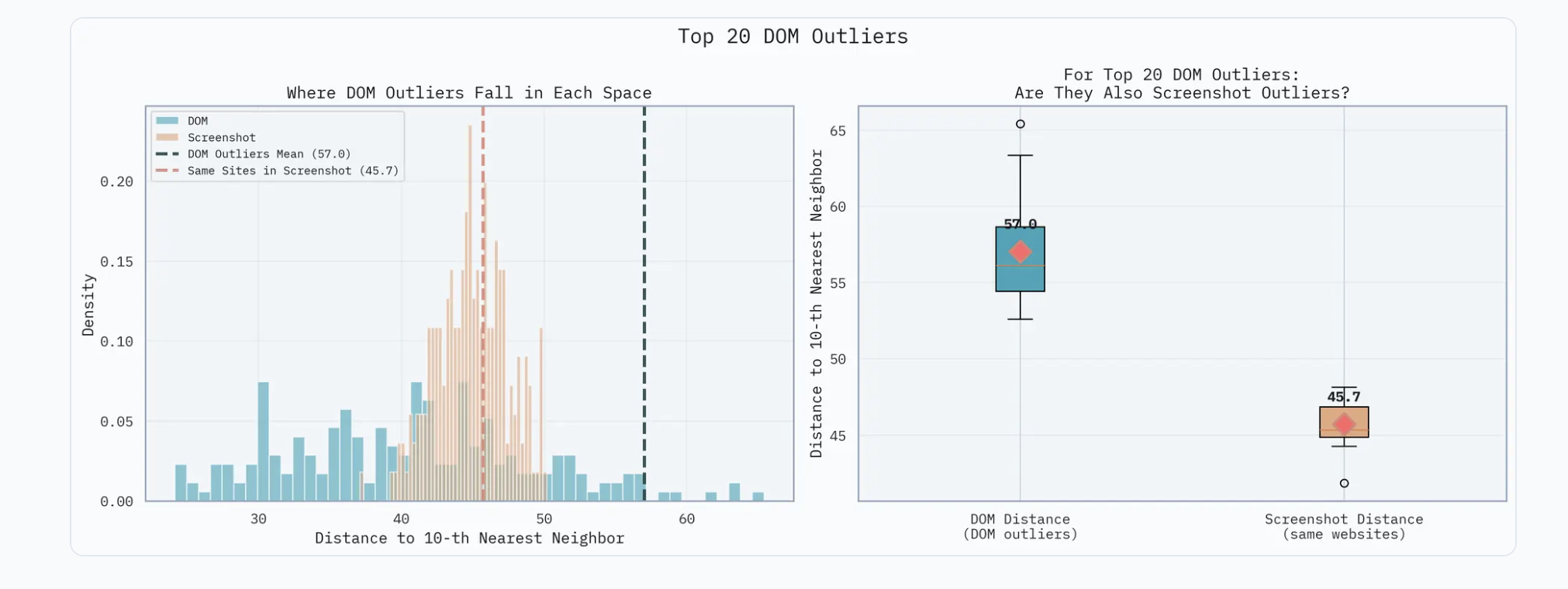

A study from Yutori found that there is an extremely high variance7 in a random sampling of 250 DOMs, while the difference in the screenshots of the UI of these pages had a much lower variance overall.

To try a text-based agent, we'll use the built in Stagehand Agent, which uses a driving model with access to 3 tools/primitives: act, observe, and extract to complete tasks on the web.

The code is very similar to the computer use agents, but instead of specifying a computer-use model, we leave that parameter blank.

// we don't specify CUA: true here to use the built-in agent

const agent = stagehand.agent({

systemPrompt: "You are a helpful assistant that can use a web browser."

});

const result = await agent.execute({

instruction: "Tell me what Stagehand.dev does."

});This agent uses a purely text-based approach (no vision). Given the DOM/A11y (Accessibility) Tree Hybrid we mentioned earlier, the agent parses it, and decides what Stagehand primitives to use to complete the task. Act completes actions on the page, observe finds and returns all possible actions on the page (clickable buttons, fillable textboxes, etc), and extract gives you customizable structured output of the page data.

Cool, now how does this change my life?

Now that we’ve covered how they work, let us talk about why they matter.

For decades, automation has required precise documentation of what needs to be automated. Think cron jobs, macros, RPA bots or hand coded scripts. Or it has meant calling various custom APIs.

Computer use models enable something different: general purpose autonomy. An AI can operate across multiple applications, across domains, and can adapt to new tasks and interfaces. You specify what you want, and the agent uses a computer to get there.

That is much larger than "run this script every night" or "call this API with these parameters".

Many valuable tasks remain manual because there is no clean API or no engineering time to build custom integration. A computer use agent can bridge that gap. If a human can do the task via the UI, the agent should be able to as well. If a computer-use agent can fill forms, collate data from ten websites, schedule meetings and log your expense reports, you spend your time interpreting results, designing systems, building relationships and solving non routine problems.

A study done by McKinsey shows AI could automate activities that take up 60–70% of current work hours, especially in knowledge-based roles. This doesn't mean those jobs suddenly vanish. Instead the repetitive parts shrink and the human attention budget can now move to creative and strategic work.

With agents, software starts to look more like a service that works for you. The control flow becomes:

Human describes an outcome → Agent interprets this and plans actions → Agent operates the software stack

Instead of learning the ins and outs of every dashboard and admin panel, you spend effort on describing goals and constraints while the agent handles the operation. This is analogous to the move from command-line interfaces to graphical ones. GUIs reduced the mental overhead of remembering long commands. Agents will reduce the overhead of endless clicking and context switching.

The future of work

Instead of humans bending their workflows around software, software, embodied as agents, begins to bend itself around human goals.

The tradeoffs between vision-based and DOM-based approaches are real. The infrastructure is still maturing. Standards and identity are being hammered out. There is still a lot of work ahead.

But the direction is clear. As AI models learn to operate computers, not just reason about them, the nature of work, software and systems shifts.

We transition from "I click the buttons" to "I describe what I want done and my agent clicks the buttons."

And when machines handle the clicking, humans get their time back for what truly matters.

→ Kyle

Footnotes

- 1.

Learn more about Reinforcement Learning

- 2.

Models that are able to take in both text & image inputs to return a response.

- 3.

Everyone defines agents differently. I define an agent as a system in which AI autonomously decides what actions/steps to take given the state it’s given.

- 4.

Early visions of software agents go back decades. Think of the "smart assistant" concepts from the 1990s. They mostly tried to suggest help while you did the work. The AI and interface capabilities simply were not there. With modern models, that vision is finally becoming practical.

- 5.

The Yutori Team. Introducing Navigator. (2025). https://yutori.com/blog/introducing-navigator

- 6.

We’re calculating the tokens using the get_encoding function from a tiktoken fork with js bindings: Repo

- 7.

Variance here is calculated by average Euclidean distance of a website to its 10 nearest neighbors using Cohere’s Embed v4 model.