Every month, Netflix streams billions of hours of video across 190+ countries. Spotify runs thousands of microservices powering 600+ million users. Google processes over 8.5 billion searches daily. How on earth do these systems not collapse under their own weight?

The answer isn't more servers. It's not a magic database or a faster programming language. It's an orchestration system; a piece of software whose sole job is to manage other software running across thousands of machines.

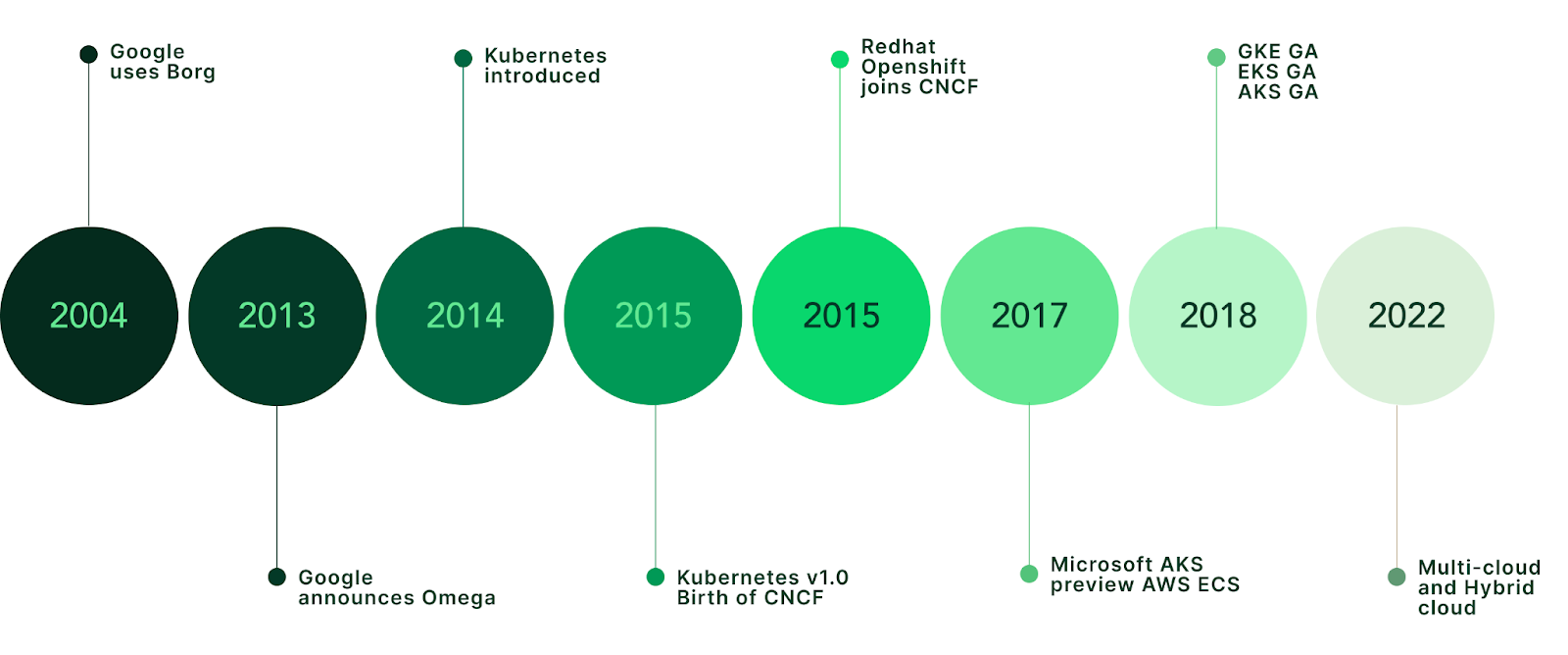

The most popular one is called Kubernetes, and it started as an internal Google project called Borg.

From Borg to Kubernetes

In 2003, Google had a problem. They were running search, ads, Gmail, and eventually YouTube on a fleet of commodity servers. Manual deployment and management was impossible at their scale. So they built Borg, an internal cluster management system that would help them orchestrate everything.

Borg was never meant to be public. It ran silently inside Google for over a decade, launching what they later revealed to be a whopping 2 billion containers per week.1

In 2013, Docker made containers accessible to everyone. Suddenly, packaging applications into isolated, portable units wasn't just a Google thing. But Docker only solved the "how do I package this app" problem, not the "how do I run 10,000 instances across 500 machines" problem.

Google saw the gap. In 2014, they announced Kubernetes (Greek for "helmsman" or "pilot")2, an open-source container orchestration system built from the lessons learned running Borg. They donated it to the newly formed Cloud Native Computing Foundation in 2015, making it cloud vendor-neutral.

Within a few years, Kubernetes became the de facto standard. AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud all offer managed Kubernetes services. The ecosystem exploded: Helm for package management, Prometheus for monitoring, Istio for service mesh.

The system Google built to run their own infrastructure is now available to everyone.

Why Orchestration?

Before Kubernetes, deploying software at scale looked something like this:

- SSH into server 1

- Pull the latest code

- Install dependencies

- Start the application

- Repeat for servers 2 through N

- Hope nothing crashes at 3am

This is imperative infrastructure management. You tell each machine exactly what to do, step by step. It doesn't scale, it's error-prone, and when something breaks, you're the one who gets paged.

Kubernetes flips this model. Instead of specifying how to deploy, you specify what you want the end state to look like:3

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: my-app

spec:

replicas: 3That's it. "I want 3 copies of my app running." Kubernetes figures out the rest; which machines to use, how to distribute the load, and even what to do when one crashes.

This is declarative infrastructure. You declare your desired state, and the system continuously works to make reality match your declaration.

The magic happens in what's called the control loop. Controllers constantly watch the actual state of your cluster, compare it to your desired state (your YAML), and take actions to fix any potential drift. If a server dies and takes two of your pods with it, the controller notices and spins up replacements on healthy machines. No one needs to get paged.

Building Blocks

Let's start with the fundamentals.

Containers

Before Kubernetes, there's Docker. A docker container is a lightweight, self-contained unit of software that includes everything needed to run: code, runtime, libraries, and dependencies.

Think of it like a literal shipping container. Before standardized shipping containers, loading cargo was chaos; different sizes, different handling requirements, different equipment. The standardized container changed global trade because any ship, train, or truck could handle ANY container.

Software containers do the same thing. But there's an important distinction: an image is the package (the blueprint), and a container is a running instance of that image. You build an image once with your app and all its dependencies, push it to a registry, then run containers from that image anywhere; your laptop, a test server, production, any cloud.

# Build a Docker image (the blueprint)

docker build -t my-app:v1 .

# Run a container from that image

docker run -p 8080:8080 my-app:v1

# Push the image to a registry

docker push myregistry/my-app:v1Pods

A Pod is the smallest deployable unit in Kubernetes. It's a wrapper around one or more containers that share storage and network resources.4

Most pods contain a single container. But sometimes you need sidecar containers; a logging agent, a proxy, a data syncer. Containers in the same pod can reach each other on localhost and share mounted volumes (filesystem).

Think of a pod as an apartment. Containers are roommates who share the kitchen and living room but have their own bedrooms.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: my-pod

spec:

containers:

- name: app

image: nginx:1.14.2

ports:

- containerPort: 80

# Second container

- name: sidecar

image: fluent/fluent-bitNodes

A Node is a machine (physical or virtual) that runs pods. Each node has a kubelet agent that communicates with the control plane and ensures containers are running as expected.

Worker nodes do the actual work; running your application containers, while the control plane nodes run Kubernetes itself.

Clusters

A Cluster is a set of nodes (both worker and control plane) working together. At minimum, you have:

- Control Plane: The brain. Stores state, makes scheduling decisions, runs controllers.

- Worker Nodes: The muscle. Actually runs your workloads.

When you run kubectl commands, you're talking to the control plane's API server, which then coordinates with worker nodes to make things happen.

Services (Stable Networking)

Pods are ephemeral, or short-lived. They come and go. They get new IP addresses each time they're created. So how do other parts of your system reliably talk to them?

Services provide stable networking endpoints.5 A Service sits in front of a group of pods and provides a single, consistent IP address and DNS name. All traffic gets automatically load-balanced across all healthy pods.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: my-service

spec:

selector:

app: my-app

ports:

- port: 80

targetPort: 8080

# Common Internal-only Service

type: ClusterIPNow instead of tracking individual pod IPs, other services just call my-service:80.

Deployments

A Deployment actually manages pods for you. You declare how many replicas (identical running pods) you want, what image to run, and the Deployment controller handles the rest.

Deployments also handle rolling updates. When you push a new version, Kubernetes gradually replaces old pods with new ones, ensuring zero downtime. If the new version is broken, you can roll back with a single command.

Hands-On: Your First Cluster

Let's actually run Kubernetes. Minikube creates a single-node cluster on your local machine.

# Install minikube (macOS)

# Installation guide: https://minikube.sigs.k8s.io/docs/start/

brew install minikube

# Start a cluster

minikube start

# Verify it's running

kubectl get nodesYou should see output like:

NAME STATUS ROLES AGE VERSION

minikube Ready control-plane 30s v1.34.0Now let's deploy something:

# Create a deployment

kubectl create deployment hello --image=nginx

# Check the pod

kubectl get podsNAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

hello-5d7b9d8c7f-x2k4j 1/1 Running 0 10sScale it up:

# Scale to 3 replicas

kubectl scale deployment hello --replicas=3

# Watch pods come up

kubectl get pods -wNAME READY STATUS RESTARTS AGE

hello-5d7b9d8c7f-x2k4j 1/1 Running 0 30s

hello-5d7b9d8c7f-m8n2p 1/1 Running 0 5s

hello-5d7b9d8c7f-q9r3s 1/1 Running 0 5sExpose it as a service:

# Create a LoadBalancer service

kubectl expose deployment hello --type=LoadBalancer --port=80

# Get the URL (minikube specific)

minikube service hello --urlYou now have a load-balanced, scalable web server running in Kubernetes. On your laptop.

How to clean up when you're done:

# Delete the service and deployment

kubectl delete service hello

kubectl delete deployment hello

# Stop the minikube cluster (frees up memory)

minikube stop

# Or delete the cluster entirely

minikube deleteScaling Deep Dive

Scaling your infrastructure is where Kubernetes really shines. There are three dimensions:

1. Horizontal Pod Autoscaling (HPA)

More pods when load increases. This is the most common approach.

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: nginx-hpa

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: nginx-deployment

minReplicas: 2

maxReplicas: 10

metrics:

- type: Resource

resource:

name: cpu

target:

type: Utilization

averageUtilization: 50Translation:

"Keep between 2 and 10 pods. If average CPU goes above 50%, add pods. If it drops below, remove pods."

The HPA controller checks metrics every 15 seconds by default. It's conservative, and won't scale down immediately to prevent thrashing.

2. Vertical Pod Autoscaling (VPA)

Bigger pods instead of more pods. The VPA adjusts CPU and memory requests/limits for existing pods.

This is useful for:

- Single-threaded applications that can't parallelize

- Workloads where pod startup cost is high

- Databases and stateful applications

apiVersion: autoscaling.k8s.io/v1

kind: VerticalPodAutoscaler

metadata:

name: my-vpa

spec:

targetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

name: my-deployment

updatePolicy:

updateMode: Auto3. Cluster Autoscaling

More nodes when pods can't be scheduled. The Cluster Autoscaler watches for pods stuck in Pending state (usually because there's not enough CPU/memory available on existing nodes) and automatically provisions new nodes from your cloud provider.

When load decreases and nodes are underutilized, it scales down by draining and removing nodes. It won't remove nodes that have:

- Non-replicated pods (like DaemonSets)

- Pods with any kind of local storage

- Pods with PodDisruptionBudgets that prevent eviction

Here's how you configure it (AWS EKS example):

apiVersion: autoscaling.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterAutoscaler

metadata:

name: cluster-autoscaler

spec:

scaleDown:

enabled: true

delayAfterAdd: 10m

unneededTime: 10m

resourceLimits:

minNodes: 2

maxNodes: 10

cores:

min: 4

max: 100

memory:

min: 8

max: 256This says:

"Keep between 2-10 nodes. After scaling up, wait 10 minutes before considering scale-down. Remove nodes that have been underutilized for 10+ minutes."

What this looks like in practice:

- HPA scales your deployment from 3→10 pods

- Some pods can't schedule (not enough resources) →

Pending - Cluster Autoscaler sees this, adds 2 new nodes

- Pending pods get scheduled to new nodes

- Later, traffic drops, HPA scales pods back down

- After 10 minutes of under-utilization, Cluster Autoscaler removes the extra nodes

This completes the scaling story:

- HPA: Scale pods within nodes

- VPA: Scale literal pod size

- Cluster Autoscaler: Scale the nodes themselves

The Control Plane: Under the Hood

Time to look at what's actually running Kubernetes.

API Server

The front door. Every kubectl command, every controller action, every node heartbeat goes through an API server. It's the only component that talks to etcd directly.

It exposes a REST API and handles authentication, authorization, and admission control.

etcd

The source of truth.6 etcd is a distributed key-value store that holds all cluster state: what pods exist, what nodes are healthy, what secrets are stored, what ConfigMaps are defined.

Everything in Kubernetes is stored in etcd. Lose etcd without backups, lose your cluster state.

Scheduler

When you create a pod, the Scheduler decides which node runs it. It considers:

- Resource requirements (CPU, memory)

- Node affinity/anti-affinity rules

- Taints and tolerations

- Current node utilization

The Scheduler doesn't actually start pods. It just assigns them to nodes by writing that decision to etcd. The kubelet on that node picks it up and does the actual work.

Controller Manager

This is where the control loops live. Each controller watches a specific resource type and works to reconcile actual state with desired state:

- Deployment Controller: Ensures the right number of ReplicaSets exist

- ReplicaSet Controller: Ensures the right number of Pods exist

- Node Controller: Monitors node health, evicts pods from failing nodes

- Service Controller: Creates cloud load balancers for LoadBalancer services

kubelet

The agent7 on every worker node. It:

- Receives pod specs from the API server

- Works with the container runtime (containerd, CRI-O) to start containers

- Reports node and pod status back to the control plane

- Runs liveness and readiness probes

Who even uses Kubernetes?

This seems like a lot, and maybe overkill for a lot of things. Kubernetes isn't just for Google-scale problems, but it helps to see who's running it at scale.

Spotify: 4,000+ microservices, migrated from their internal Helios system. They run multiple clusters across regions with thousands of nodes.

Pinterest: 250,000+ pods across their clusters. They built their own Kubernetes platform team and tooling.

Airbnb: Moved from a monolithic Rails app to Kubernetes-based microservices. They standardized on Kubernetes across all environments.

Why do companies choose Kubernetes?

The appeal starts with vendor neutrality. You can run the exact same workloads on any cloud (AWS, GCP, Azure, or your own data center). Start on one cloud, move to another if pricing changes or requirements shift. No rewriting application code, no vendor lock-in.

Then there's the ecosystem. Helm charts for package management, Prometheus for metrics, Istio for service mesh, ArgoCD for GitOps deployments. The tooling around Kubernetes is unmatched because everyone standardized on it. Need to solve a problem? There's probably already a well-maintained open-source tool for it.

But the real operational win is self-healing. A pod crashes? Kubernetes automatically restarts it. A node dies? Pods get rescheduled to healthy nodes within seconds. A deployment has a memory leak? Set resource limits and it'll get killed and restarted before taking down neighbors. This happens without the engineers getting paged at 3am.

Finally, it's declarative everything. Your entire runtime environment (deployments, services, secrets, config) lives in version-controlled YAML. Want to see what changed when the site went down? git diff. Want to roll back? Revert the commit. It's infrastructure as code, but for the entire stack, not just the VMs.

The Bigger Picture

Kubernetes is more than a deployment tool. It's a paradigm shift in how we think about infrastructure.

The same patterns that power Google Search, that run Netflix's 400+ million hours of monthly streaming, and handle Spotify's 4,000 microservices; are also available to anyone who learns to write YAML and think declaratively.

From Google's Borg managing billions of containers to you running kubectl on your laptop, the abstraction is the same. The infrastructure complexity is hidden behind a clean API.

We went from manually SSHing into servers to declaring our infrastructure using code. That's not just automation; that's a fundamental shift in how we think about running software.

The learning curve is real. The YAML is verbose. The networking will make you question your career choice at least once. But once it eventually clicks, you'll have access to the same infrastructure patterns used by the largest companies in the world.

→ Kyle

Footnotes

- 1.

The Borg paper was published in 2015 at EuroSys. It says that Google launches over 2 billion containers per week.

- 2.

'Kubernetes' is often abbreviated as 'K8s' (pronounced "kay-ates"). This is a numeronym where 8 represents the eight letters between 'K' and 's'. Similar patterns: i18n (internationalization), a11y (accessibility).

- 3.

Declarative vs Imperative: In imperative programming, you specify how to achieve a result step by step. In declarative programming, you specify what result you want and let the system figure out how. SQL is declarative ("give me all users where age > 21"), while a for-loop filtering an array is imperative.

- 4.

Pod Internals: Pods are implemented using Linux kernel features: namespaces (for isolation of network, PIDs, mount points) and cgroups (for resource limits). Containers in the same pod share the network namespace (they can reach each other on localhost) and can share volumes.

- 5.

Service Types: Kubernetes offers several Service types: ClusterIP (default) exposes the service on an internal IP only reachable within the cluster. NodePort exposes on each node's IP at a static port (30000-32767). LoadBalancer provisions an external load balancer (cloud provider specific). ExternalName maps to a DNS name. Services use label selectors to determine which pods receive traffic.

- 6.

etcd: A distributed key-value store that uses the Raft consensus algorithm to maintain consistency across multiple nodes. It stores all cluster state: pod specs, secrets, configmaps, service accounts. The name comes from the Unix "/etc" directory (for configuration) + "d" for distributed.

- 7.

Resource Limits and OOMKilled: Without resource limits, a single pod can consume all CPU/memory on a node, starving other pods. Kubernetes uses requests (guaranteed minimum) and limits (hard ceiling). If a container exceeds its memory limit, the kernel's OOM (Out of Memory) killer terminates it; you'll see "OOMKilled" in pod status. CPU limits work differently: the container gets throttled, not killed.